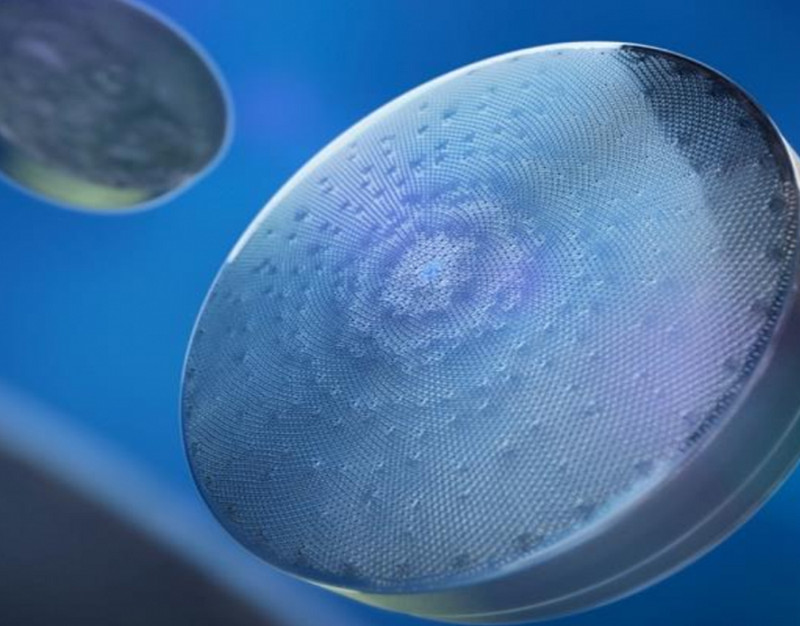

Silica: from stardust to the living world

Silica. So why are we interested in this element? Because it is particularly abundant in the form of silica and silicate minerals on the planet Earth and on the terrestrial planets (Mercury, Venus, Mars, etc.). But, in this case, why are living organisms based on carbon and not on silicon? Is there any chance of encountering silicon-based life somewhere in the universe? If living organisms on planet Earth are carbon-based, do they also contain silicon? Are these silicified organisms important for marine life and for the carbon cycle in the ocean? How has this evolved over time?

All these questions, and more, are answered by the Silica School, organised by Dr Jill Sutton and Professor Paul Tréguer ( Institut Universitaire Européen de la mer, University of Brest). It opened on 26 October 2020 with the support of ISblue.

The “Silica School” currently brings together more than 30 marine research institutes and universities from 12 different countries and continues to develop. It is a SPOC (Small Private Online Course), in which some fifty students from France, China, the United Kingdom, North America, Australia, etc. have registered for this first edition.

The main objective of the Silica School, subtitled “Silica: from stardust to the living world”, is to highlight the current level of knowledge on silica research by offering an interdisciplinary course to students of the universities and institutes members of the Silica School Consortium. In ten courses, silica in the universe, in the ocean, in the living world, and in the future are successively covered.

It provides students with access to online lectures, course materials and instructor contact information via question and answer forums to encourage interaction between students and instructors who are international silicon experts in the fields of chemistry, biology, geology and physics.

“Listening to the first lecture, its content and presentation is fan-tas-tic!”, wrote a student from the University of Bristol (UK)

Each course is available online to allow students to learn about each concept at their own pace. The total time to cover the whole course varies according to each student’s background and the topics covered (normally 32 hours). Up to 30 hours of personal work is expected.

The online courses include specific instructions for students to engage in different tasks (discussion forum, individual assignments) and/or quizzes to both help the student practice and assess understanding.

Attention, vous utilisez un navigateur peu sûr !

Attention, vous utilisez un navigateur peu sûr !